Sorry if this newbie question has been asked before, but could not find an answer via the search.

I am very curious to why you get totally different results using low & slow as opposed to higher & faster?

When cooking a pork tenderloin on the grill using indirect heat (and smoke) for a about 1½-2 hours at 225F until core temp is about 190F, I will get a very nice and juicy dinner. But if I cook it at direct heat for 20-30 minutes it will be dry and boring at the same core temp of 190F. Same with a pork roast in the oven - if I give it 320F for about 2 hours until core is 190F and use the broiler to get the cracklings puffed, then I have a juicy roast. But using the traditional roasting method with 400F for 1h 15 min and using broiler, renders the meat dry. It is nice to know how to cook better using low & slow, but I really would like to understand why this happens...

So I'm wondering why the big difference in results happens?

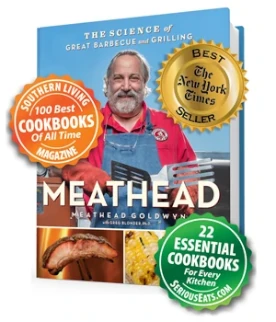

I know that high & fast can make it easier to overcook the meat, but assuming we hit the same core temperature, why is there such a difference? I assume that temperature, time and total energy transfer are variables in this as explained in Meatheads book, and that energy transfer at different temperatures may be both different and non-linear curves, but if we hit the same energy transfer by having the same core temp, why is there such a difference in juiciness? Is it related to the fact that surface area meat transfer heat to the core meat which is mostly water, and temperatures too high will evaporate more water than those just above the boiling point?

Cheers, Lars

I am very curious to why you get totally different results using low & slow as opposed to higher & faster?

When cooking a pork tenderloin on the grill using indirect heat (and smoke) for a about 1½-2 hours at 225F until core temp is about 190F, I will get a very nice and juicy dinner. But if I cook it at direct heat for 20-30 minutes it will be dry and boring at the same core temp of 190F. Same with a pork roast in the oven - if I give it 320F for about 2 hours until core is 190F and use the broiler to get the cracklings puffed, then I have a juicy roast. But using the traditional roasting method with 400F for 1h 15 min and using broiler, renders the meat dry. It is nice to know how to cook better using low & slow, but I really would like to understand why this happens...

So I'm wondering why the big difference in results happens?

I know that high & fast can make it easier to overcook the meat, but assuming we hit the same core temperature, why is there such a difference? I assume that temperature, time and total energy transfer are variables in this as explained in Meatheads book, and that energy transfer at different temperatures may be both different and non-linear curves, but if we hit the same energy transfer by having the same core temp, why is there such a difference in juiciness? Is it related to the fact that surface area meat transfer heat to the core meat which is mostly water, and temperatures too high will evaporate more water than those just above the boiling point?

Cheers, Lars

Comment